Best Practices When Driving a Race Car

Best Practices When Driving a Race Car

I do quite a bit of driver coaching whether that is in real life or on a simulator and I find myself saying a lot of the same things to different clients. That’s because there is a lot to pay attention to when driving a race car at speed! In this article I’m going to go over some of the best practices when driving a race car. These are in no particular order.

Eyes Up

If a driver keeps missing their apexes then chances are they don’t have their eyes up, meaning they aren’t looking for enough ahead. The car is going to go where the driver is looking and if they aren’t looking for the apex soon enough then the car isn’t going to get there. I recognize that there is a lot going on at 100+ mph but the faster you go the more important this is.

As a driver is approaching their braking point they obviously have to look for that point and get on the brakes when they get there. But once they know that they are going to be braking at the correct point, their eyes should be looking for the apex (maybe even before they start braking). And once they are sure that they are going to make the apex, they should be looking for where they want their car to be at the exit (this is usually before the car actually gets to the apex). I use virtual reality in my simulator and I find that this really helps me to practice this. As a side note, I know a lot of drivers use a turn-in point and if it works for them then that’s great. I personally have never really used turn-in points because I have always relied on my eyes to tell me when to turn.

Open The Radius

The reason why Opening The Radius (or using all of the track) is important is simple – the more steering is used the slower the car goes. A tight radius is associated with a slow corner, correct? Unless there is some sort of feature on the track that is preventing the driver from opening the radius or if there is a line benefit (such as a more important corner upcoming), then there is no reason to not open the radius. It is easy time off of the clock!

Lifting

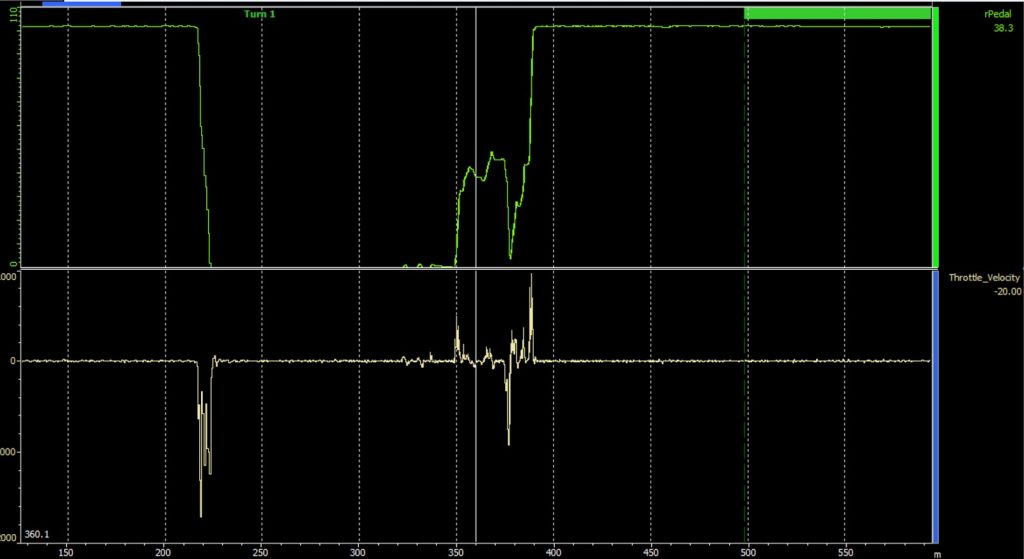

Unless a driver is going from throttle to the brake, shifting a manual car, or lifting for a high speed corner instead of braking, lifting should be a red flag. If a driver has gotten to the apex of the corner and goes to throttle and then lifts then that means that something just happened that the driver didn’t like – either consciously or subconsciously. Many times this means that the car is understeering and that lift transferred weight to the front tires in order to give them a little more grip. It could also mean that the driver did not take the correct line into the corner and paid for it by having to lift while exiting. Or it could mean that the driver simply tried to go to throttle too soon – but again, there is a reason for the lift and it is important to identify the reason. This is something that is easily identified in the data so don’t ignore it. Exhibit 1 shows an example of a driver lifting after the initial throttle application exiting a corner.

Brake Release

I have talked about this many times before but the brake release (trail braking) is what determines how quickly the weight comes off of the front tires and transfers to the outside tires. The end of braking (EOB) is when the foot comes off of the brake pedal and the driver decides if the car needs a little bit of a coast or if it is ready for throttle application. Once you feel like you have perfected the brake release for a particular corner, stick with it. If you feel like you are over slowing, brake a little later but try to keep the same brake application and release. If you are feeling rushed or missing the apex then try braking a little earlier, again, with the same braking technique. Exhibit 2 shows a great brake trace for a slow corner where trail braking is required.

Steering Velocity

In order to drive a race car fast the driver needs to have fast hands — but only when absolutely necessary. The initial turn of the steering wheel into a corner should be much slower than the speed required to catch the back end of the car if it steps out. But sometimes changing the speed at which you turn the steering wheel can make all the difference in the world in regard to driving fast through a corner. A car with a soft suspension can handle a faster turn-in than a stiffer car. And sometimes it pays to get the outside tires loaded with slow hands and then faster hands as soon as the driver knows that the weight has shifted to the outside tires. This is especially true in high-speed corners when the driver is entering the corner while on the throttle.

Exhibit 3 shows what this might look like in the data. The data is from me driving a USF 2000 car at Summit Point Raceway, WV using iRacing on my simulator. Summit Point was my home track many years and Turn 3 is a fast corner that takes a little finesse at corner entry to get it right. It begs you to turn in early but if you do that then you will most likely run out of track at the exit. Like all formula cars, the USF2000 has a stiff suspension so it reacts very quickly when the driver turns the steering wheel. For Turn 3, I purposely try to load the outside tires and get the lateral g’s building before turning the car more so that I can take a later apex.

In Exhibit 3, I have used vertical lines to indicate what is happening in the data. I have steering and lateral G’s overlapped at the top of the chart so that it is easy to see that they track together. However, I changed the scale of the steering trace to -20 degrees to +20 degrees so that this is seen easier. The corner radius trace indicates when the car has started turning and this aligns with the steering input. Note that at this point the steering velocity has hardly changed and the car’s heading hasn’t changed much either. Shortly after I started turning into the corner, there was a slight correction that I frankly don’t remember but shows up in the corner radius and steering traces. This phase has now loaded the outside tires and I know I can input more steering. I steer the car a little faster and the heading changes faster as well. All of this is done in .7 seconds and 130 ft!

Understeer and Oversteer

To be really quick, the driver has to be able to identify how the car is handling at entry, middle, and exit of every corner. This is important because at entry the majority of the weight is on the front tires, in the middle the weight is primarily on the outside tires, and at the exit the weight is primarily on the rear tires. Where the weight is helps determine what setup change to make if one is required. One question that I frequently ask my clients is: If there is one thing that the car could do better, what would it be? That one question usually leads to a discussion about the car’s handling at different parts of the track. I normally calculate the understeer and oversteer of the car so I can usually have a pretty good idea of how the car is handling but it sure helps to have a driver that can provide feedback so that the calculations can just be validation.

I have had a number of clients blame themselves for not being as fast as they should be. And many times, that is true — but not always. For example, if the car starts understeering as soon as the driver starts applying throttle then that driver is going to have to lift off of the throttle and that is all it takes to lose time. So, if a setup change can be made to take away some of that understeer while exiting a corner, then naturally the driver is going to be faster. As mentioned before, having to lift should be something that the driver recognizes. Maybe he can drive the car a little differently (such as taking a later apex) to avoid lifting or maybe this is a clue that the car has too much understeer exiting the corner.

Oversteer is easy to identify because it is easy to feel the back end stepping out. But maybe the car has just enough oversteer to cause the driver to feel unsure about whether or not the back end is going to step out. I have seen this with drivers in high-speed corners. The best setup is the one that gives the driver the most confidence. If the driver isn’t comfortable with the car and there is nothing they can do differently (besides driving the car slower) than whatever is making the driver uncomfortable needs to be addressed. In this case, if the car has a rear wing then a little bit more downforce in the rear can make all the difference in the world.

Understeer is harder to identify than oversteer. Again, the driver having their eyes up and looking far ahead can help them identify understeer because if the car is not going where they are looking then that is another clue the car that the car might have too much understeer. But one thing that I see a lot of is drivers inducing understeer. If the driver is applying throttle (positive throttle velocity) and the driver is applying steering (positive steering velocity) and the car has understeer then the driver is most likely inducing it. That is why it is important to unwind the steering wheel while applying throttle. Exhibit 4 shows what induced understeer might look like in the data. My math channel states that if the understeer is greater than 3 degrees and steering velocity and throttle velocity are both increasing then return a 1. The pink spikes show the induced understeer. In this case, I would only be concerned with the first two spikes because the driver is unwinding the steering wheel and the understeer is decreasing when the last 3 spikes appear.

There also may be a situation where the car has understeer at a particular corner but it is not possible to adjust the car to help the car handle better. If the driver drives the car hard into the area and ends up reacting to the understeer by lifting off of the throttle then they are just slowing themselves down. It is far better to come to the realization that the car is going to understeer there every lap and be proactive about how to deal with it. In this case a better approach might be to go to some throttle before the understeer starts but then pause the throttle application just before the understeer starts. Once the understeer has subsided then the driver can then continue applying throttle. This is what is shown in Exhibit 5.

There also may be a situation where the car has understeer at a particular corner but it is not possible to adjust the car to help the car handle better. If the driver drives the car hard into the area and ends up reacting to the understeer by lifting off of the throttle then they are just slowing themselves down. It is far better to come to the realization that the car is going to understeer there every lap and be proactive about how to deal with it. In this case a better approach might be to go to some throttle before the understeer starts but then pause the throttle application just before the understeer starts. Once the understeer has subsided then the driver can then continue applying throttle. This is what is shown in Exhibit 5.

Stick with me, I’m almost there! All I need now is the distance from the GPS Point to the Braking Point. I want to calculate the distance only when the GPS Point to Brake Point trace is equal to 1. Therefore, this is the math channel that I used to do this: IF(“GPS Point To BP”[#] == 1, LAP_INTEG(“GPS Point To BP”[#])* (“GPS Speed”[mph]/3600) *5280,0). This states that if the GPS Point to Brake Point is equal to 1, then take the integral of the GPS Point to Brake Point value and multiply it by the formula to get feet from mph. Exhibit 5 shows this trace in green on the time/distance graph and in red on the track map.

Good Luck in your races!